Stroke can’t strike out teen

ER and neuro teams hit home run with treatment used for first time at Wolfson Children’s.

Article Author: Juliette Allen

Article Date:

Thirteen-year-old Carlos Ortiz’s father describes him as a strong, athletic kid. So when Carlos told his dad he wasn’t feeling well after an evening baseball practice in January 2020, his father listened.

“He told me that at the end of practice, he started feeling like his left leg went numb and the left side of his body was feeling kind of weird,” said Carlos’ father, also named Carlos Ortiz. “He lost vision on his left side, had a headache and was feeling dizzy. It was not the normal Carlos that I see after baseball practice.”

From the ball field to the ER

Sensing the urgency of the situation, the two decided to go to Baptist Medical Center South, where a new Wolfson Children’s Emergency Center, providing specialized emergency care for children, had opened just a week earlier.

“They did some bloodwork and some imaging, and the doctor came back and said it might be a stroke,” Ortiz said. “I just couldn’t believe it. I started crying. It was the worst experience that I’ve ever been through. Just seeing my kid, a healthy 13-year-old, and hearing the word ‘stroke,’ it was hard to believe.”

Carlos was immediately transported to Wolfson Children’s Hospital’s main campus downtown via Kids Kare Mobile ICU, where a team was waiting to take him directly to the MRI Suite. Carlos’ MRI confirmed a stroke.

Code Stroke

Harry Abram, MD, pediatric neurologist with Wolfson Children’s Hospital and Nemours Children’s Health, Jacksonville, and medical director of the Brunell Family Children’s Neuro-Diagnostic Center, has worked to streamline the stroke protocol to alert critical clinical staff of a patient having a possible stroke and facilitate the fastest response possible.

He, along with critical care specialists in the Wolfson Children’s Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU), pediatric anesthesiologists, endovascular surgeons and pediatric radiologists, received an alert on their pagers as soon as the ER physician at Wolfson Children’s Emergency Center at Baptist South called the Pediatric Stroke Hotline, which is only used for children having a potential stroke. Because of this process, everyone was in place and ready by the time Carlos arrived at Wolfson Children’s Hospital.

“I really applaud the team at Wolfson Children’s Emergency Center at Baptist South who recognized the symptoms as a potential stroke and acted immediately,” said Dr. Abram. “It saved time, which is so critical when a patient of any age is having a stroke.”

“Super -perfect” circumstances

Time was particularly important in this case because Dr. Abram knew Carlos could be an ideal candidate to receive the blood clot-busting medication, tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), which is commonly used in adults but rarely in children.

“The circumstances have to be just perfect to give it to an adult, and to give it to a child, it has to be super-perfect,” said Dr. Abram. “All the cards have to line up and the pieces have to fall into place perfectly.”

A child has to be given intravenous tPA within 4-1/2 hours of the onset of stroke. Due to the public perception that children don’t have strokes, Dr. Abram said many parents will wait to seek emergency care for their child. In this case, though, Carlos’ father and care team immediately recognized the symptoms and acted quickly, which allowed him to qualify for the treatment.

“This is the first time we have given tPA to a child at Wolfson Children’s Hospital, and it’s only been given to a child 25 or so times in the U.S.,” said Dr. Abram. “It’s a one-hour infusion, and 45 minutes into it, Carlos’ vision had completely returned to normal and he could move his left arm.”

Heart of the matter

Although Carlos’ symptoms improved, the biggest question remained: what caused the stroke? As part of the process to figure that out, Jose Ettedgui, MD, former pediatric interventional cardiologist with Wolfson Children’s C. Herman and Mary Virginia Terry Heart Institute, performed an echocardiogram, a test that creates images of the heart.

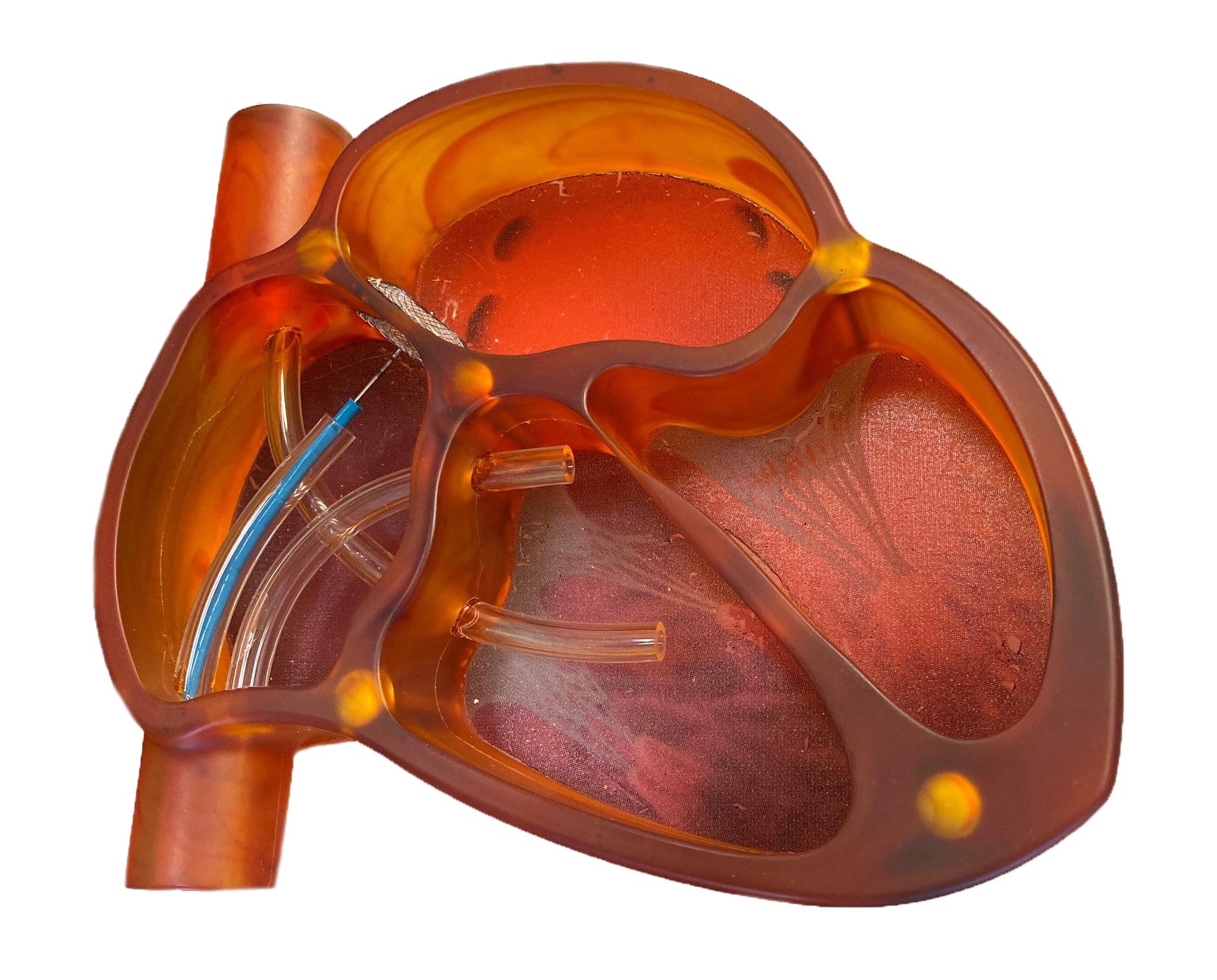

“There’s a naturally existing hole in the wall of the heart before birth that, with the change in the dynamics of blood flow from being inside the womb to being in the outside world, should seal off once a baby is born,” said Dr. Ettedgui. “When the hole doesn’t close, it’s called patent foramen ovale (PFO). Through testing, we found that Carlos has PFO.”

While the term “hole in the heart” sounds scary, Dr. Ettedgui said PFO is relatively common, occurring in 20-25% of people, with the vast majority having no major problems from the condition. In Carlos’ case, however, the hole may have allowed a blood clot to travel straight to the brain, causing the stroke.

“The hole is just the pathway,” said Dr. Ettedgui. “What can happen is, somewhere in the deep veins of the leg or pelvis, a very small blood clot is produced. As that clot is traveling through the bloodstream, if it goes through the heart at just the right time, it can go from the right side, through the hole and then to the left side. Once it’s on the left side, the majority of blood flow ejected from the heart goes north to the brain. That can cause a stroke.”

Dr. Ettedgui performed a minimally invasive procedure to insert a wire mesh patch to close off the hole in the heart in February 2020. He said it should be the only procedure Carlos will need.

“Once the device has been implanted, after the first six months or so, the cells that form the inner layer of the heart will grow over it,” said Dr. Ettedgui. “It acts as a framework for the heart to finish healing itself.”

Getting back in the game

After the stroke, Carlos spent one night in the PICU before being transferred to the Neuroscience floor of Wolfson Children’s for three more nights. In the long run, Carlos will be able to return to the baseball diamond about a month after his heart procedure, though he will initially need to wear a helmet at all times due to blood thinners he is taking.

While Carlos’ father is still coming to grips with what he calls a roller coaster of events, he is grateful for the fast actions that set Carlos up for the best outcome possible.

“I’m so appreciative of the way both the Wolfson Children’s Emergency Center at Baptist South and Wolfson Children’s Hospital acted so quickly to get Carlos into the position to receive the tPA,” he said.

For Dr. Abram, Carlos’ story is a reminder to parents that, while rare, strokes do happen in children.

“Most of what we do in neurology is after the fact. We see a child after they’ve been in a car accident, after they’ve had meningitis, or a couple days after a stroke, and we really can’t do much. We just support the parents and do the best we can,” he said. “So for us to be able to go in there and really make a difference at the time of the stroke with revolutionary medicine is a really rewarding for the whole team.”

Minutes matter when your child is having a health emergency, which is why Wolfson Children’s has six Emergency Centers located throughout the Northeast Florida area. To find the nearest Wolfson Children’s Emergency Center, along with wait times, visit wolfsonchildrens.com/emergency.